“We lack shared beliefs, ideals and aspirations about what Kenya can become if we all subscribed to a national ethos that builds and reinforces our unity,” states the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) report when tackling the burning question of ethos.

In simpler terms, the Task force found out that fifty-seven years after independence, we don’t have a”character” to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize our community, nation or ideology.”

And this is no surprise. We are country that doesn’t still have a clear cultural policy. Well, maybe not true because in 2009, the late Hon William ole Ntimama launched the first of its kind National Policy on Culture and Heritage. This was 46-years late. I am of the opinion that we still don’t have a sound national policy on culture and heritage because in 2010, we gave ourselves a new Constitution that “recognized culture as the foundation of the nation and as the cumulative civilization of the Kenyan people and nation” but the policy is not aligned to the new constitutional realities.

The Constitution’s philosophy, vision, design and architecture and many other related articles spoke to culture and the reawakening that should have in essence informed the revision of the 2009 Policy. A process to do this was initiated by cultural workers but to date, the process has never moved beyond the Cabinet Secretary’s desk after it got stuck there during the infamous Hassan Wario’s era. We will not even mention his successor because there was zero attempt to deal with matters culture.

For once in the country’s 57-years history as an independent state, the Ministry of Culture has been extensively cited and recognized. The BBI report places a lot of responsibility on harnessing and nurturing of the national ethos to this Ministry. The report recommends the strengthening of “the Ministry of Culture and Heritage to build and promote cultural policies that are linked to the Counties’ promotion of cultural activities. The Ministry should also be able to do more to document, protect, and promote ancient and historical monuments of national importance.”

It also adds: “The Ministry of Culture and Heritage should use public participation and input from experts to codify an official pantheon of Kenyan heroes who reflect Kenya’s values and ethos, our fight for democracy and freedom, our aspirations and our outstanding achievements. These heroes should be included in museum displays, curriculums and displays.”

The BBI report now makes these and a raft of other recommendations that will help shape the national culture but fails to look at the opportunities that the Constitution offers in redefining our national ethos. It is now increasingly becoming clear that a clamour to change the Constitution is going to be part of the intended process to fix the national ethos. However, would satisfactory and honest implementation of the Constitution have helped in curing the maladies that the BBI now wants to cure? The Constitution as an instrument for change is not duly recognized.

The preamble lays the foundation of what is expected of us in nation building and setting national ethos. It speaks about the past, honouring “those who heroically struggled to bring freedom and justice to our land”; ethnic, cultural and religious diversity; environmental concerns and our aspirations. The things that we need to honour like the sovereignty of the people, the supremacy of the constitution, what each citizen is expected to do in defence of the constitution. It speaks to our expected language—national and official, the national values and principles. It was envisaged that sincere implementation of the Constitution, entrenching Constitutionalism would have helped shape the national ethos.

There is no doubt that an honest look at what the Constitution sort to achieve is at the very center of everything that the BBI hopes to achieve. The BBI is therefore not seeking to cure anything that we don’t know or have not tried to put a mechanism to correct. The BBI simply echoes the long-held belief that there is a dire need to deliberately positively shape our national character but will to do this never there.

This is sad but real. If the noise, name calling, trading of accusations, suspicions, manipulation and all other vices that have characterized the rallies, meetings and engagements of the BBI process is anything to go by, then this assertion is true. No sooner had this announcement been made during its dramatic launch at Bomas, than the country moved back to its default mode of behaving badly.

And therein lies the challenge of the task ahead of implementing some of the recommendations that have been suggested in the report and those that will be presented in the second round of gathering views. We have very good proposals on paper on what needs to be done to change things. There is clarity of what needs to be done to reengineer our society. However, “kwa ground” on implementation, “mambo ni different.”

What does Cultural Reengineering Really Entail?

Developing a national ethos calls for a deliberate, well-planned, well-resourced, widely supported and soundly executed process to reengineer our cultural psyche. It calls for change. However, change is not always easily embraced and welcomed. It is even harder if those expected to lead in the charge for change are the greatest beneficiaries of the current system that favours them.

The BBI report as it stands has made this call. It notes: “This report is a historic opportunity for us to begin willingly defining, developing and subscribing to an enduring collective vision that would lead to a united Kenya equal to all its major challenges. It would appreciate and honour excellence in leadership, in the civic practices of citizenship, and in our care and consideration of one another. Such an ethos would be deeply respectful of differences in culture, heritage, beliefs and religions. Its character would guide and constrict the planning and actions of the State to the benefit of the people of Kenya. The journey to developing such a national ethos begins by accepting the desperate need for it. That is the most important recommendation made in this report.”

“This report is a historic opportunity for us to begin willingly defining, developing and subscribing to an enduring collective vision that would lead to a united Kenya equal to all its major challenges. It would appreciate and honour excellence in leadership, in the civic practices of citizenship, and in our care and consideration of one another. Such an ethos would be deeply respectful of differences in culture, heritage, beliefs and religions. Its character would guide and constrict the planning and actions of the State to the benefit of the people of Kenya. The journey to developing such a national ethos begins by accepting the desperate need for it. That is the most important recommendation made in this report.”

Cultural reengineering as suggested in the report will require that we disembark from the bus we are currently travelling in. The BBI report as it stands currently, is clear that this bus that we have boarded is full of bad things. It is full of con men. It is full dishonest men and women. We are intolerant of each other. We week to exploit others. We would not feel anything if we are sitting on two seats and others are standing on the aisles. To attain change, a lot needs to change too.

With this reality in mind, how easy can the recommendations that the BBI makes be embraced by all considering that they stand a chance of throwing things upside down? If honestly implemented, the out will probably alter some long-held truths?

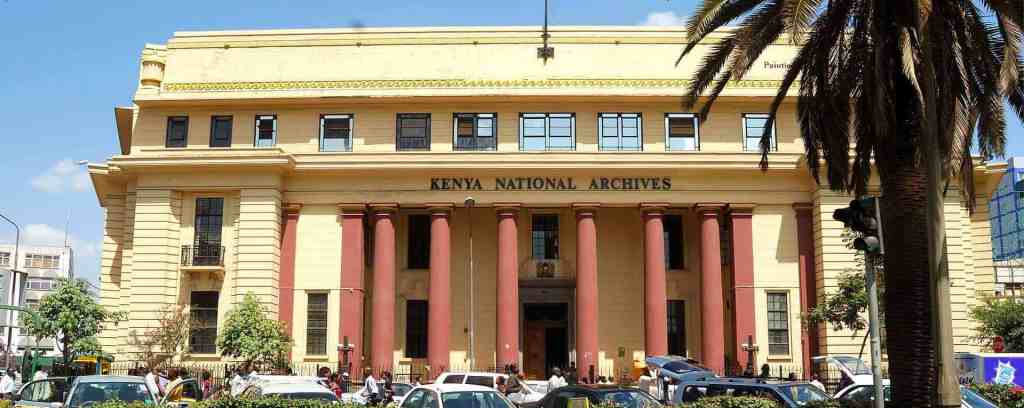

For instance, the BBI notes that we should give ourselves a definitive, evolving, and inclusive official historyi.e. an official and inclusive history. The report says: “H.E. President Uhuru Kenyatta should commission an Official History of Kenya whose production will be led by an Office of the Historian resident in the National Archives. This history should go back 1000 years and provide an accurate and definitive account of the settlement of Kenya by the present inhabitants; the political, economic, and cultural histories of all ethnic groups in Kenya; the role of women throughout this history; an account of the international slave trade and colonialism; the anti-colonial struggles; the post-colonial history of every part of the country; and contemporary histories including those of urban areas and newly formed communities in Kenya.”

A noble idea. However, how would the history of those who betrayed the country and the the people’s cause during the struggle for independence be treated? Would we have the courage to tell the truth about people who sold out the country and the ideals of the struggle but later on became glorified as the founding fathers and mothers of the nation? Would this be revisionist history or factual even if it hurts and debunks some myths that have been perpetuated over time?

Brutally Honest

Would we be brutally honest with historical facts? The way out requires that the reengineering is guided by honesty and the truth therein sets us free. It should not be limited to our communities and people alone. We should also revisit the values or vices that shaped the country’s colonial era and later on adopted and perpetuated in the independent state. In revisiting and rewriting history as the BBI recommends, we must also revisit and discuss the foundation, architecture and design of the modern-day state of Kenya.

A new national ethos cannot be realized if we don’t also address the country’s political economy. The political-economy that has shaped every sphere of our nation’s building effort was by and large designed during the colonial era and later perpetuated by the New Kenya Group as described by Colin Leys in his book Underdevelopment in Kenya— The Political Economy of Neo-Colonialism.

The ideas and ideals that went into shaping how land would be managed, involvement in commerce and industry, leadership, agriculture, running of government, the government’s responsiveness to the citizens, etc. were based on a colonial fallacy.

The current coronavirus pandemic might have slowed the action around BBI and especially the rallies but when it resumes, the hard questions on the way the national ethos will be realized, should be asked. A practical way that will answer this national question should be outlined during the rallies and in the final report that will be developed.

Born Keinan Abdi Warsame in 1978, K’Naan is the grandson of Haji Mohamed, one of Somalia’s most famous poets; he is also a nephew of famed Somali singer Magool .”If you’re going to make music I think it should contribute in some way,” he said in an interview with Africa Success website. “It doesn’t have to change the world, it could just be a good melody. My experiences aren’t just mine, it’s just that I can articulate them in English, it is also about the lives of people who have suffered,” as he and his family have.

Born Keinan Abdi Warsame in 1978, K’Naan is the grandson of Haji Mohamed, one of Somalia’s most famous poets; he is also a nephew of famed Somali singer Magool .”If you’re going to make music I think it should contribute in some way,” he said in an interview with Africa Success website. “It doesn’t have to change the world, it could just be a good melody. My experiences aren’t just mine, it’s just that I can articulate them in English, it is also about the lives of people who have suffered,” as he and his family have.